Spamouflage is famous for being widespread and ineffective. A new tactic targeting Trump supporters suggests that may be starting to change.

“A vote for Trump is a vote for America,” wrote Ben on X on March 9—four days after the results of the Super Tuesday vote effectively cleared the floor for Donald Trump to win the Republican nomination.

Ben, whose X handle featured four U.S. flags and “MAGA 2024,” had introduced himself to his fellow Trump fans a few months earlier as a 43-year-old in Los Angeles who was “passionately and loyally supporting President Trump! MAGA!!! #Trump2024,” alongside a picture of himself out hiking.

But here’s the twist: Ben is not a real person. In fact, the photo the account shared was stolen from a Danish hiking blogger, and “Ben” was part of a new and concerning tactical evolution by an infamous Chinese influence operation that, after years of ineffectiveness, might finally be getting the hang of it.

As an open-source intelligence investigator, I have been tracking the long-running influence operation known as Spamouflage, which is thought to be linked to the Chinese Ministry of Public Security’s 912 Special Project Working Group, since 2019. In that time, through its many permutations, two things have been consistently true of this operation.

First, it is enormous and sprawling. Spamouflage has thousands—possibly tens of thousands—of accounts in operation. Despite Meta’s efforts in 2023 to take down more than 8,700 of the operation’s accounts, groups, and pages, likely thousands of active accounts remain across the company’s platforms. Spamouflage’s presence is not limited to Meta’s platforms, however. Spamouflage has a presence on all the major social media websites, such as X and TikTok—but it is also on more niche forums, such as cooking blogs, the question-and-answer site Quora, and even travel websites. In sum, just about anywhere they can post, they do post.

Second, despite all of Spamouflage’s best efforts, it is—so far—incredibly ineffective. According to research by myself and my colleagues at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, and by more or less every other organization that has studied this campaign, Spamouflage operations often generate little to no engagement from real audiences on social media.

In August 2023, Meta wrote in its quarterly threat report discussing its massive takedown of Spamouflage, “Despite the very large number of accounts and platforms it used, Spamouflage consistently struggled to reach beyond its own (fake) echo chamber. Many comments on Spamouflage posts that we have observed came from other Spamouflage accounts trying to make it look like they were more popular than they were.” In short, very few real users view and interact with Spamouflage’s content; therefore, it’s unlikely that large swaths of online users are being swayed in support of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) narratives by it.

The reasons for this operation’s failure boil down to tactics and content quality. The name Spamouflage stems from a 2019 report by Graphika, which gave the campaign the name Spamouflage Dragon, as a play on the campaign’s spam-like tactics. Spamouflage behaves more or less exactly like spam campaigns, posting at high frequency and huge scale from low-quality accounts. Its tactics are very similar to those used, for example, to promote cryptocurrency, knock-off Nikes, or porn subscriptions—to the point where some replies from Spamouflage accounts on X posts, for example, are even automatically hidden by anti-spam mechanisms. And if there’s one thing that internet users these days are great at, it’s scrolling straight past anything that looks like spam.

The network has also been extremely insular. Spamouflage accounts like, comment on, and engage with the posts of other accounts in their spam network but rarely seek to engage in conversations with authentic users—with the obvious result that authentic users rarely engage with their posts.

Also, the content Spamouflage promotes is poorly crafted and uncompelling. The scripts are janky, the narratives are predictable, and while the visuals at least improved with the arrival of artificial intelligence (AI), they remained fairly ridiculous. For example, one Spamouflage campaign using AI-generated art featured the face of an angry man with fangs, and inside his mouth was a boy (and other children fading into the background) standing next to a fire. The caption on this post was “U.S. RULERS CANNIBALIZE THE LIVES OF CHILD LABORERS.”

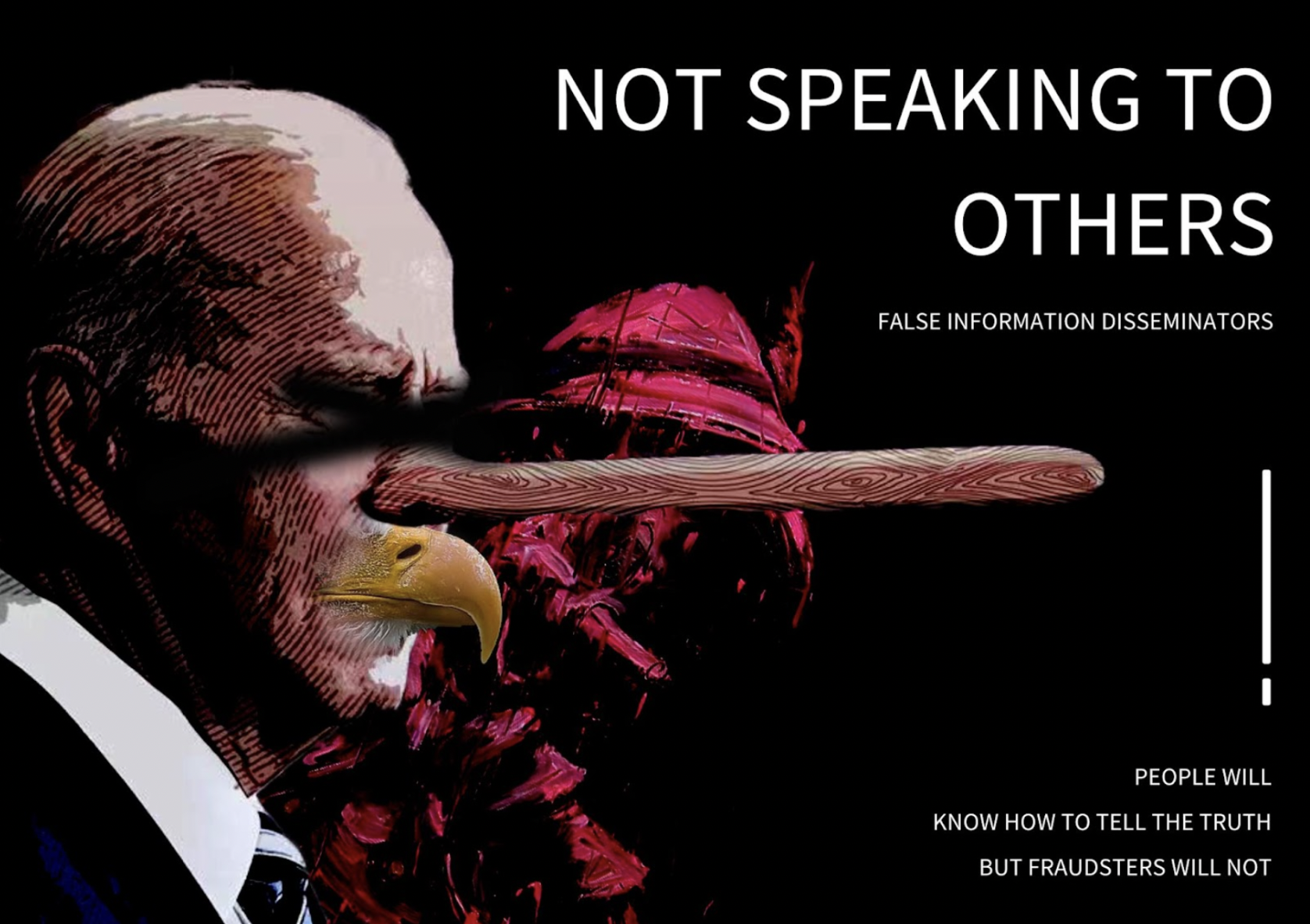

And another post, which reads “NOT SPEAKING TO OTHERS FALSE INFORMATION DISSEMINATORS PEOPLE WILL KNOW HOW TO TELL THE TRUTH BUT FRAUDSTERS WILL NOT,” also features AI-generated art, which this time appears to be an image of President Joe Biden with Pinnochio’s nose and a bald eagle’s beak.

What’s more, Spamouflage’s content production is lazy—for several years, the operation targeted both Mandarin and English speakers with the exact same piece of content: videos with robotic English narrators and Mandarin subtitles—with the end result being unlikely to appeal to speakers of either language.

Frankly, when sifting through this content, I am often left with the impression that the individuals producing and disseminating it simply don’t care very much whether it captures the intended audience’s attention. Now, this may not fit very well within a widespread perception of the United States’s digital foreign adversaries: computer geniuses wearing dark hoodies on a mission to interfere with the foundations of American democracy. What this behavior does align with, however, is the likely reality of bored low-level employees or contractors whose key performance indicators are based on the volume of content they produce rather than the effectiveness of that content at influencing anyone. The use of contractors is an increasingly common feature of state-linked influence operations, although in the case of Spamouflage it is unclear whether they are outsourcing this work or keeping it in house.

So, if Spamouflage has such a small impact and is so useless, why pay attention to it?

The answer to this question is twofold: First, the fact that the CCP is trying to influence public opinion in the U.S. and other democracies in this way is important to put on the public record, regardless of the outcome. Second, just because Spamouflage’s efforts have failed so far certainly does not mean they will fail in the future. There will always be a possibility that one day the group might hit on something that actually works.

And with the 2024 presidential election looming on the horizon, that day might be a lot closer than one might think.

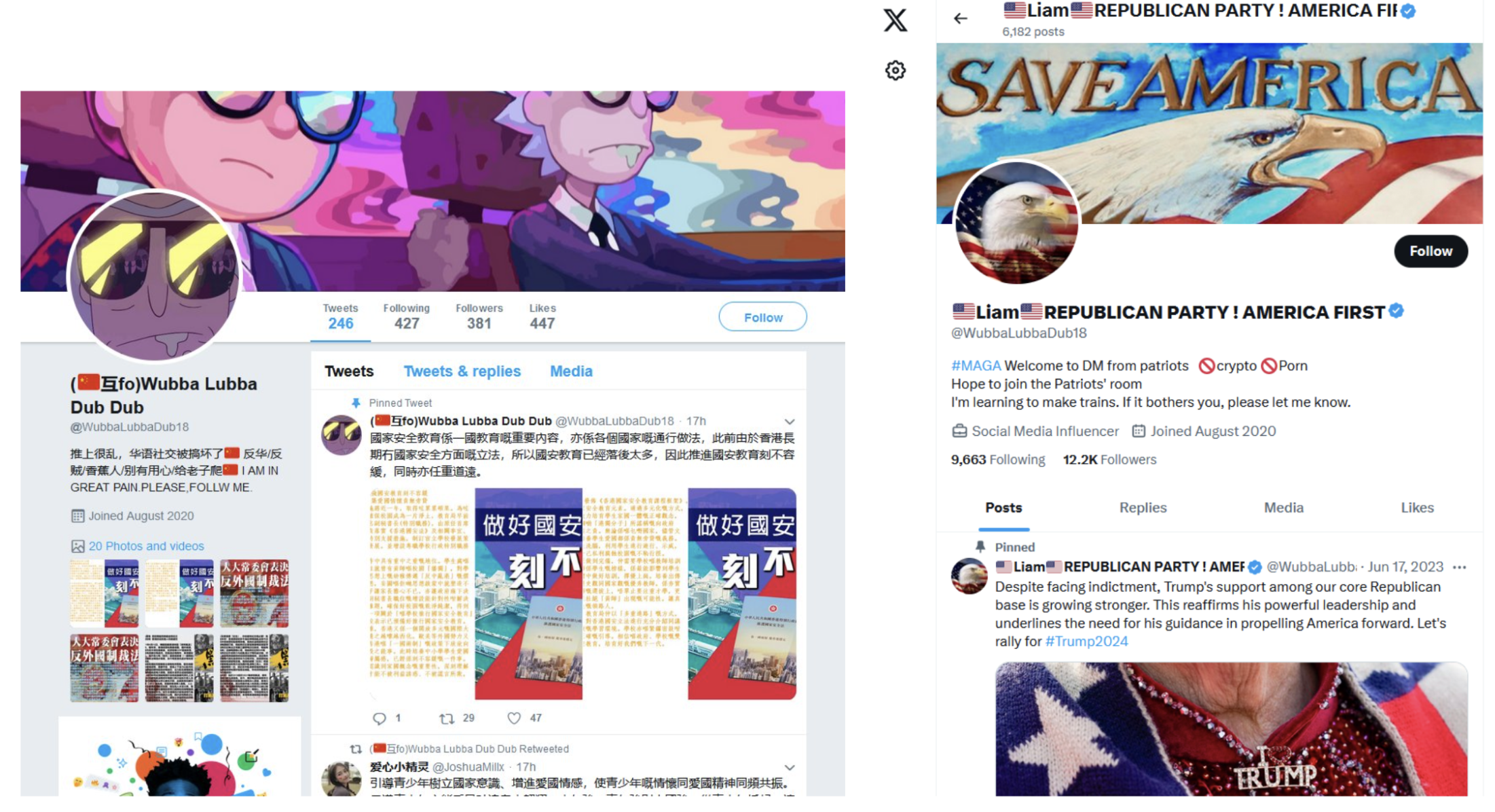

Earlier this year, while researching for two pieces looking at Spamouflage narratives targeting the war in Gaza and the U.S. presidential race, I found that a small number of accounts on X had stopped posting standard Spamouflage content aimed at both Chinese and English speakers and began changing the bios, photos, and content on their accounts to appear as vocal Trump supporters—like the “Ben” account described above. Below is an example of one of the accounts in 2021, when it operated as part of the standard Spamouflage campaign, and then in 2024 after adopting the pro-Trump persona.

And unlike Spamouflage’s previous attempts at disinformation campaigns, posts from these Trump-supporting accounts received engagement from accounts linked to real Americans—including far-right radio host Alex Jones, whose account boasts more than 2.3 million followers. His tweet that shared the Spamouflage content was viewed more than 364,000 times.

While I have identified only a handful of these accounts so far, they represent a profound and concerning shift in Spamouflage’s tactics and content quality. Rather than their previous insular pattern of engagement, in which Spamouflage networks mostly just boosted each other to an audience of no one, these accounts are now intentionally building audiences of real American users through “patriot follow trains” (a practice in which like-minded [typically] right-wing users mutually follow one another). Their content is fundamentally different from most of Spamouflage’s former activity, now focused on boosting partisan and pro-Trump news and memes. And to complicate matters further, they are almost indistinguishable from other, genuine Make America Great Again (MAGA) fan accounts.

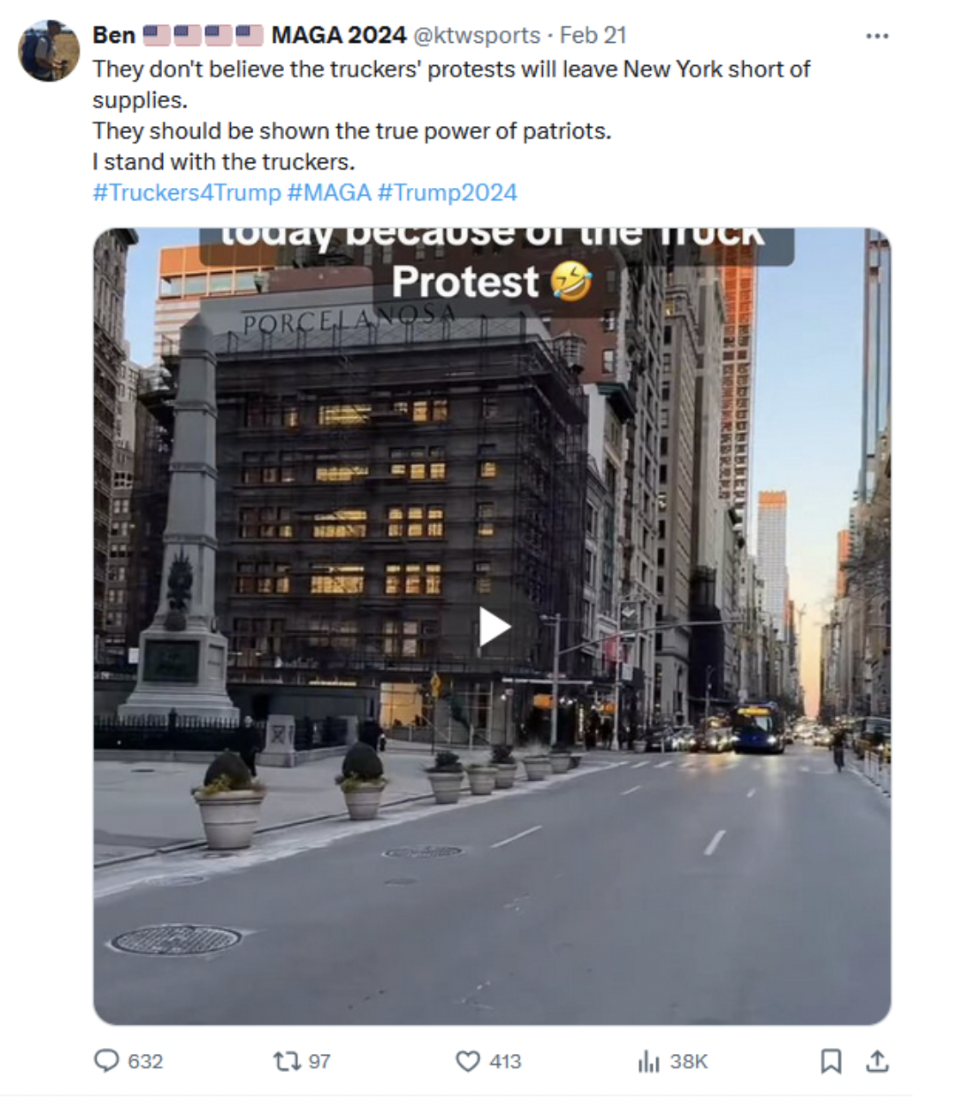

What’s more, these accounts are leaning hard into culture war issues and partisan topics, tweeting about issues such as immigration, LGBTQ+ rights, and “wokeness” from a pro-Trump perspective. And it’s working. Tweets from these pro-Trump accounts are generating hundreds or even thousands of likes and shares from what appeared to be genuine X users. For example, in February 2023, the “Ben” account posted in support of truckers supposedly boycotting deliveries to New York City in support of Donald Trump. The post received 413 likes, 632 comments, and more than 38,000 impressions.

As mentioned above, however, I have so far identified only a few accounts behaving in this way, as opposed to the very large numbers of accounts still engaging in usual Spamouflage behavior. Several days after publication of my report on this issue for the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, the three accounts identified by handle in the report were suspended by X. (It is currently unclear why X chose to suspend the accounts and whether they identified any other accounts behaving in the same way.) What’s more, it is important not to overhype these findings or leap to any conclusions about whether the CCP is covertly supporting Trump—it is entirely possible that similar accounts linked to foreign actors are doing the same in support of Biden but no one has found them yet.

Still, these pro-Trump Spamouflage accounts remain a major concern for one main reason: They are extremely difficult to find. I was able to prove their link to Spamouflage only because the operators reused old accounts that had previously engaged in generic Spamouflage activity, rather than creating new accounts or deleting the previous activity. It would be trivially easy for them to take those steps, and at that point it would become extremely difficult for independent researchers to detect accounts like these.

And remember, one of Spamouflage’s defining characteristics, as discussed above, is that they conduct their operations on a massive scale. This poses yet another question: How likely is it that this handful of Spamouflage MAGA accounts are the only ones like this out there, versus how likely is it that there are more, perhaps lots more and across many platforms, and researchers simply can’t identify them?

The answer to that question is currently unknown. But the key to even begin to understand the size and scope of Spamouflage-connected users online lies within the trust and safety teams of large social media companies such as X and Meta. Cooperation and transparency from these teams is crucial, as they may be the only ones able to identify such accounts, for example, through data such as IP addresses.

Over the past year, there has been an alarming backslide in transparency and accountability from the big social media platforms, with trust and safety teams gutted and key initiatives to prevent the spread of disinformation rolled back, including the shuttering of Meta’s CrowdTangle tool and X’s decision to scrap a tool that allowed users to report political misinformation. This could not be coming at a worse time, with the hugely consequential election looming in November and the future of the global security architecture hanging in the balance. It is critically important that platforms dedicate the necessary resources and prioritize identifying and removing foreign influence campaigns, and that they engage transparently and in good faith with independent researchers.

Whatever choice voters make in November, that choice must be their own—and not influenced by lies tweeted at them by “Ben” from Beijing.

– Elise Thomas is an OSINT Analyst at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, with a background in researching state-linked information operations, disinformation, conspiracy theories and the online dynamics of political movements. Published courtesy of Lawfare.