In the wake of the U.S. killing of a top Iranian general and Iran’s retaliatory missile strike, should the U.S. be concerned about the cyberthreat from Iran? Already, pro-Iranian hackers have defaced several U.S. websites to protest the killing of General Qassem Soleimani. One group wrote “This is only a small part of Iran’s cyber capability” on one of the hacked sites.

Two years ago, I wrote that Iran’s cyberwarfare capabilities lagged behind those of both Russia and China, but that it had become a major threat which will only get worse. It had already conducted several highly damaging cyberattacks.

Since then, Iran has continued to develop and deploy its cyberattacking capabilities. It carries out attacks through a network of intermediaries, allowing the regime to strike its foes while denying direct involvement.

Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-supported hackers

Iran’s cyberwarfare capability lies primarily within Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, a branch of the country’s military. However, rather than employing its own cyberforce against foreign targets, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps appears to mainly outsource these cyberattacks.

According to cyberthreat intelligence firm Recorded Future, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps uses trusted intermediaries to manage contracts with independent groups. These intermediaries are loyal to the regime but separate from it. They translate the Iranian military’s priorities into discrete tasks, which are then bid out to independent contractors.

Recorded Future estimates that as many as 50 organizations compete for these contracts. Several contractors may be involved in a single operation.

Iranian contractors communicate online to hire workers and exchange information. Ashiyane, the primary online security forum in Iran, was created by hackers in the mid-2000s in order to disseminate hacking tools and tutorials within the hacking community. The Ashiyane Digital Security Team was known for hacking websites and replacing their home pages with pro-Iranian content. By May 2011, Zone-H, an archive of defaced websites, had recorded 23,532 defacements by that group alone. Its leader, Behrouz Kamalian, said his group cooperated with the Iranian military, but operated independently and spontaneously.

Iran had an active community of hackers at least by 2004, when a group calling itself Iran Hackers Sabotage launched a succession of web attacks “with the aim of showing the world that Iranian hackers have something to say in the worldwide security.” It is likely that many of Iran’s cyber contractors come from this community.

Iran’s use of intermediaries and contractors makes it harder to attribute cyberattacks to the regime. Nevertheless, investigators have been able to trace many cyberattacks to persons inside Iran operating with the support of the country’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Cyber campaigns

Iran engages in both espionage and sabotage operations. They employ both off-the-shelf malware and custom-made software tools, according to a 2018 report by the Foundation to Defend Democracy. They use spearfishing, or luring specific individuals with fraudulent messages, to gain initial access to target machines by enticing victims to click on links that lead to phony sites where they hand over usernames and passwords or open attachments that plant “backdoors” on their devices. Once in, they use various hacking tools to spread through networks and download or destroy data.

Iran’s cyber espionage campaigns gain access to networks in order to steal proprietary and sensitive data in areas of interest to the regime. Security companies that track these threats give them APT (Advanced Persistent Threat) names such as APT33, “kitten” names such as Magic Kitten and miscellaneous other names such as OilRig.

The group the security firm FireEye calls APT33 is especially noteworthy. It has conducted numerous espionage operations against oil and aviation industries in the U.S., Saudi Arabia and elsewhere. APT33 was recently reported to use small botnets (networks of compromised computers) to target very specific sites for their data collection.

Another group known as APT35 (aka Phosphoros) has attempted to gain access to email accounts belonging to individuals involved in a 2020 U.S. presidential campaign. Were they to succeed, they might be able to use stolen information to influence the election by, for example, releasing information publicly that could be damaging to a candidate.

In 2018, the U.S. Department of Justice charged nine Iranians with conducting a massive cyber theft campaign on behalf of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. All were tied to the Mabna Institute, an Iranian company behind cyber intrusions since at least 2013. The defendants allegedly stole 31 terabytes of data from U.S. and foreign entities. The victims included over 300 universities, almost 50 companies and several government agencies.

Cyber sabotage

Iran’s sabotage operations have employed “wiper” malware to destroy data on hard drives. They have also employed botnets to launch distributed denial-of-service attacks, where a flood of traffic effectively disables a server. These operations are frequently hidden behind monikers that resemble those used by independent hacktivists who hack for a cause rather than money.

In one highly damaging attack, a group calling themselves the Cutting Sword of Justice attacked the Saudi Aramco oil company with wiper code in 2012. The hackers used a virus dubbed Shamoon to spread the code through the company’s network. The attack destroyed data on 35,000 computers, disrupting business processes for weeks.

The Shamoon software reappeared in 2016, wiping data from thousands of computers in Saudi Arabia’s civil aviation agency and other organizations. Then in 2018, a variant of Shamoon hit the Italian oil services firm Saipem, crippling more than 300 computers.

Iranian hackers have conducted massive distributed denial-of-service attacks. From 2012 to 2013, a group calling itself the Cyber Fighters of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam launched a series of relentless distributed denial-of-service attacks against major U.S. banks. The attacks were said to have caused tens of millions of dollars in losses relating to mitigation and recovery costs and lost business.

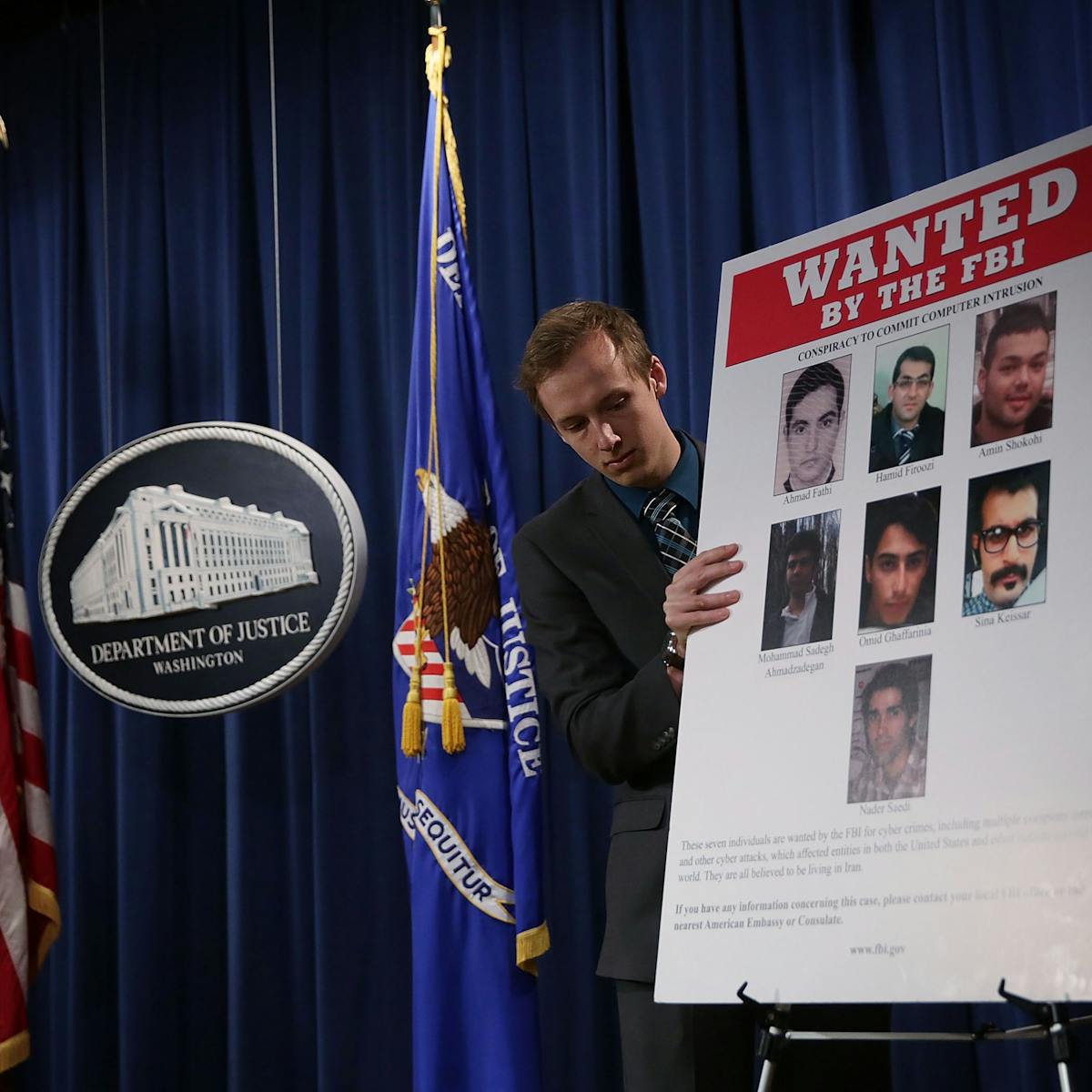

In 2016 the U.S. indicted seven Iranian hackers for working on behalf of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps to conduct the bank attacks. The motivation may have been retaliation for economic sanctions that had been imposed on Iran.

Looking ahead

So far, Iranian cyberattacks have been limited to desktop computers and servers running standard commercial software. They have not yet affected industrial controls systems running electrical power grids and other physical infrastructure. Were they to get into and take over these control systems, they could, for example, cause more serious damage such as the 2015 and 2016 power outages caused by the Russians in Ukraine.

One of the Iranians indicted in the bank attacks did get into the computer control system for the Bowman Avenue Dam in rural New York. According to the indictment, no damage was done, but the access would have allowed the dam’s gate to be manipulated if it not been manually disconnected for maintenance issues.

While there are no public reports of Iranian threat actors demonstrating a capability against industrial control systems, Microsoft recently reported that APT33 appears to have shifted its focus to these systems. In particular, they have been attempting to guess passwords for the systems’ manufacturers, suppliers, and maintainers. The access and information that could be acquired from succeeding might help them get into an industrial control system.

Ned Moran, a security researcher with Microsoft, speculated that the group may be attempting to get access to industrial control systems in order to produce physically disruptive effects. Although APT33 has not been directly implicated in any incidents of cyber sabotage, security researchers have found links between code used by the group with code used in the Shamoon attacks to destroy data.

While it is impossible to know Iran’s intentions, they are likely to continue operating numerous cyber espionage campaigns while developing additional capabilities for cyber sabotage. If tensions between Iran and the United States mount, Iran may respond with additional cyberattacks, possibly ones that are more damaging than we’ve seen so far.

Dorothy Denning, Emeritus Distinguished Professor of Defense Analysis, Naval Postgraduate School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.