.png?sfvrsn=2f011ea5_5)

This article draws from our paper “Digital Discrimination of Users in Sanctioned States: The Case of the Cuba Embargo,” published for the 2024 USENIX Security Symposium with the Distinguished Paper Award.

Cuba has one of the world’s most digitally repressive regimes. The government blocks many digital platforms, including Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Telegram; it also has among the slowest internet speeds globally and limited internet penetration. Udemy, a prominent learning platform, is inaccessible in Cuba. So is Spotify—with podcasts like “Cuban Family Roots” and “History of the Cuban Revolution”—and Zoom, the world’s most popular online video conferencing service. But it’s not the Cuban government that’s blocking these services—it’s the platforms themselves.

Faced with ambiguous and evolving rules about how to operate in sanctioned states, websites voluntarily de-risk and block users from their platforms through location-based discrimination. The U.S. has tried to promote internet access and combat censorship in Cuba; in May, the U.S. government again clarified how sanctions apply to digital platforms. However, our new research shows for the first time the true scale of geoblocking. Digital equality is about not just differences in infrastructure and censorship but also whether websites themselves allow users to access their platforms.

State Challenges to the Liberal Internet

How people get information and communicate, and whether their governments can restrict or shape information, is central to liberal governance. Repressive governments censor the press, ban or surveil activists, and prevent mass protest. With the development of the internet, people were able to find information from sources outside government control, advocate from behind anonymous screen names, and organize in private messaging groups. But the internet’s wide-eyed liberal moment came to an end quickly as governments either shut down access when it threatened their survival or censored users through blocking and filtering.

Combating internet repression has been a major U.S. policy goal for 30 years. The U.S. supports a worldwide internet freedom agenda, spending $30 million a year on initiatives at the State Department, USAID, and the Broadcasting Board of Governors (now the U.S. Agency for Global Media). The internet freedom agenda was just another program in a long line of efforts to promote democracy through disrupting repressive governments’ stranglehold on information.

The U.S. has invested significant resources in Cuban information access since the Cuban Communist Party came to power in 1959. The most famous of these efforts is Radio and TV Marti, produced by the Office of Cuba Broadcasting. According to the Government Accountability Office, between 1983 and 2011 the U.S. government provided over $660 million to fund the programs.

The U.S. hopes the internet will unlock new sources of information and communication for Cuban citizens; leaked U.S. diplomatic cables suggested that online bloggers would be a serious challenge to the Castro regime. Cuba’s first internet connection in 1996 with Sprint was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation. President Obama emphasized internet accessibility in Cuba during his famous Havana speech in 2016. In 2019, a Presidential Advisory Committee tasked with promoting Cuban internet access recommended building a new submarine cable to Cuba.

In 2021, faced with domestic protests, the Cuban government restricted access to Facebook and WhatsApp. In response, President Biden announced his administration would work “with the private sector to identify creative ways to ensure that the Cuban people have safe and secure access to the free flow of information on the internet.” Ideas included using high-altitude balloons fitted with satellite internet technology to provide censorship-free internet access to Cubans. This would revive a Google project called Loon balloons, which provided balloon-based internet services in rural Kenya and Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. The administration also discussed providing Cubans with free access to VPNs (a tool that hides internet traffic).

The U.S. thought that it could promote digital freedom and equality by increasing the censorship costs for repressive governments and giving citizens the tools to stay online. But it has become increasingly clear that’s not enough.

Sanctions and the Digital Economy

Economic sanctions are intended to prompt citizens to lobby their governments to change policies, elites to pressure their peers, or leaders to anticipate unrest and bend to external pressure. The U.S. imposed and expanded embargoes on Cuba in response to Cuba’s nationalization of American companies and agricultural reforms (1959-1963), the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion (1961), and the 1996 shootdown of Brothers to the Rescue aircraft. Sanctions were designed to weaken the Cuban Communist Party’s power, creating the conditions for a democratic transition, pro-U.S. foreign policy, and the return of seized foreign assets.

However, sanctions cause collateral damage for ordinary citizens in targeted states. Research shows that everything from per-capita income, to inequality, to infant mortality and human rights suffer in sanctioned states. Sanctions can even cause repressive states to double-down in order to limit threats to their regimes.

Digital rights groups have suggested that sanctions might undermine internet access in repressive states. This isn’t necessarily because sanctions would prompt government crackdowns, but because sanctions might deprive ordinary citizens of digital services from sanctioning states. The U.S. government recognizes the risks sanctions create for digital freedom and has subsequently passed general licenses to enable those services.

We study U.S. sanctions against Cuba, some of the most comprehensive in the world. They feature several general licenses to facilitate access to digital platforms. We specifically address websites and digital platforms in this research. However, there are additional general licenses for telecommunications equipment and internet service provider interconnection. Licenses focus on two aspects to differentiate digital platforms—how widely available they are and whether they provide educational services.

The U.S. first issued a digital services general license for Cuba in 2010 (31 CFR 515.578), authorizing services and software for online activities including email, instant messaging, sharing media, and web browsing. However, “such services and software must be publicly available at no cost to the user’’ and cannot be provided to a “prohibited official of the Government of Cuba … or a prohibited member of the Cuban Communist Party.” In other words, websites could allow Cubans on their free websites, but not prohibited members of the Cuban government. No paid services could be offered in Cuba.

In 2015, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) published an expanded version of 515.578, removing the requirement that services be publicly available at no cost to the user. Additionally, services “widely available to the public at no cost” could be provided to normally prohibited officials of the Cuban government or Cuban Communist Party (31 CFR 515.578(a)(4)(i)). This would allow Cubans on paid websites, prohibited members of the Cuban government on free websites, and kept in place limitations for Cuba Restricted List entities on paid websites.

In 2015, the general license for educational activities (515.565) added (p. 569122) “Provision of internet-based courses, including distance learning and Massive Open Online Courses, to Cuban nationals, wherever located.” This enabled Cubans to pay for online learning courses, although it was unclear how it applied to restricted individuals.

In May 2024, OFAC provided additional information (although no substantive changes) for digital platforms and services. They included guidance on digital services that could be considered “widely available to the public at no cost to the user” including e-learning platforms, automated translation, and video conferencing. OFAC also clarified what counts as “due diligence” for identifying prohibited members: Companies “may reasonably rely on information provided to them by their customers in the ordinary course of business.”

As we interpret the government’s intentions, no free websites should be blanket geoblocked in Cuba. Websites offering only paid services should be available, blocking prohibited members of the Cuban Communist Party and entities on the Cuba Restricted List from purchasing services. Websites offering both free and paid services should allow anyone onto the free services but prevent prohibited members of the Cuban Communist Party or entities on the Cuba Restricted List from purchasing the paid version. The reality is very different.

De-risking as a Threat to Internet Freedom

Despite clarifying how to provide digital services in sanctioned states, internet freedom continues to suffer due to digital platforms’ de-risking strategies. Websites routinely de-risk by blocking all internet users in Cuba from accessing their platforms. Ironically, many of these websites are operated by states pushing internet freedom and openness. The tension between access to free information and the risks companies face in an uncertain market creates a significant barrier to digital freedom.

Discovering whether a website is inaccessible is simple. The hard task is figuring out why—is it a technical error or the web host, or is the government blocking access through internet filtering in cooperation with internet service providers? Alternatively, the website could refuse the connection on the basis of a user’s location—this is called geoblocking. It’s simple to enact: A website administrator configures their system to refuse connections from IP addresses geolocated to a given country, such as Cuba. This is how websites, rather than governments, block users.

The last time Cuban geoblocking was in the news, a spokesman for Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) expressed skepticism, telling Time magazine, “The U.S. sanctions specifically do not apply to telecommunication …. It is the regime that is blocking access to it and reporting otherwise is to parrot their propaganda.” The nonprofit United Against Nuclear Iran called geoblocking into doubt, stating that “[c]laims that sanctions continue to impede Iranian activists’ access to the internet are baseless.” For a while, evidence of widespread geoblocking was anecdotal. Our research shows how widespread it really is.

We identified geoblocking of Cuban users by over 500 domains—including 142 of the internet’s top 2,000 most popular domains, 77 percent of which are headquartered in the U.S. This includes services such as Spotify, Zoom, Webex, Adobe, Codecademy, and PayPal.

This is an opaque process. Although 39 percent of the top 2,000 domains discuss sanctions compliance somewhere on their websites, nearly 90 percent of geoblocking domains did not provide geoblocked Cuban users information on why they are blocked. Users see a server error, but nothing else. This creates confusion for internet users in Cuba trying to determine the cause. Our methods confirm widespread blocking due to servers refusing customers, rather than government censorship or poor infrastructure.

Websites provide different services (e.g., financial, educational, technology) and have different access models (paid, free, “freemium”). Geoblocking due to sanctions could make sense in the narrow circumstances in which the website can be used only for prohibited services. For example, many U.S. banks (Visa, Bank of America, Wells Fargo) geoblock Cuba, but a bank’s website controls financial accounts, which are highly regulated under existing sanctions and have significant compliance costs.

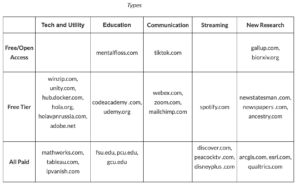

We focus on two services that Cubans should be able to access—free services that anyone can access on the internet and education resources. U.S. general licenses cover these services specifically. Table 1 features websites blocking Cubans separated by the service type and access model.

Some websites, like WinZip, Zoom, and Mental Floss, geoblock by serving a block page with a 403 Forbidden error to indicate server-side denial of the request. The user-facing clarity can vary from the minimal “Access Denied” to more detailed compliance disclosures, like Mental Floss’s blockpages, which includes “you appear to be located in a country or region where we do not provide services.” Others, like TikTok, use the “451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons” error to specifically address the legal motivations for the blocking.

Even websites offering completely free services and information—without requiring an account—geoblock Cubans. This includes websites like bioRxiv, a free online archive for life sciences papers operated by a nonprofit research institution and supported by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Cuban health researchers are at the forefront of cancer and diabetes research, but the entire country is blocked from accessing a free medical paper archive. There is no circumstance where sanctions should apply to this site, yet it blocks all Cubans.

Websites that are free to access, but do sell services, also block Cubans. Gallup is one of the largest public opinion polling firms in the world. While it offers products (custom reports, advanced analytics), the website itself contains detailed news reporting that is not behind a paywall. It is inaccessible to Cubans; for example, an article on U.S. public opinion toward normalized relations could not be read in Cuba. This isn’t because the Cuban government doesn’t like what the article says, but because Gallup configured its website to refuse Cuban users.

Websites offering both free and paid-tier subscriptions often geoblock instead of funneling Cuban users into their free versions. This happens across media platforms like Spotify, communications channels like Zoom, Webex, or Mailchimp, or basic digital utilities like WinZip and Unity. Websites offering VPN services, including Hola, block Cubans, denying them tools to bypass government censorship. In these cases, geoblocking directly undermines Cubans’ ability to avoid other forms of censorship. Rather than enact a more sophisticated compliance program, these sites choose to block all Cubans.

Educational resources should be accessible in Cuba under a general license (515.565). However, free and open (Mental Floss) and free-tier (Codeacademy, Udemy) educational websites geoblock Cubans. Universities offering online courses, including Florida State University, prevent Cuban users from accessing their platforms. Pima Community College, one of the largest community college networks in the U.S., and Grand Canyon University, one of the largest for-profit universities in the U.S., block Cubans.

Solutions

The market for access to open information failed the Cuban people. Even if the Cuban government didn’t block any websites, and Cuba had a robust internet infrastructure with fast and inexpensive access, users would be unable to access numerous digital resources because of server-side discrimination. Despite licenses to promote access to free services and educational resources, as well as published guidance on sanctions, websites voluntarily restrict users in sanctioned states.

Why haven’t efforts to enable free and widely available platform access worked? We have two ideas. First, online platforms have limited experience with sanctions compliance. This is why companies de-risk by geoblocking rather than by enacting a more sophisticated compliance system. Second, by creating a separate category for “widely available to the public at no cost,” the government implied that access to such a service could be subject to sanctions. If a general license can be granted for such services, it can also be taken away. This language does not appear in any other part of the U.S. sanctions regime, and it remains unclear how it applies.

Say I run an email service and First Secretary of Cuba Miguel Diaz-Canel registers for an account. If the service is completely free, he can sign up for an account and use it as much as he wants (as long as my service is “widely available”). I should not have to monitor whether he even has an account. If I have an additional paid tier, and he registers for a free account, it is likely permissible; but if he opts for the paid tier and purchases services from me, it is illegal.

However, if the government ever reforms 31 CFR 515.578(a)(4)(i) to restrict members of the Cuban Communist Party again, even if my website is completely free and widely available, I have no way to know whether I’m in compliance. I would have to design my entire site to manage future risks, not just the current ones. Or I could prevent any Cubans from accessing the site and avoid risking noncompliance.

While the above case is clearly difficult to unravel, why are educational platforms (both free and paid) blocked? One explanation is the condition for the online education general license. Services are allowed “provided that the course content is at the undergraduate level or below.” However, there is no definition for these levels. Undergraduate level might depend on the institution, or the content. Some content is taught to both undergraduates and graduate students. Some courses have both a graduate and undergraduate version with the same lectures but different assignments.

To combat widespread geoblocking, we offer several recommendations.

Reform and Clarify the CFR

Instead of creating exemptions for free and widely available services, clarify whether companies providing access to free services would fall under any existing embargo or sanction rules. Exempting some groups also implies that free services could be subject to sanctions. We advocate exempting any free and widely available service from both country-based and SDN (specially designated nationals and blocked persons) sanctions.

Alternatively, if the Treasury Department wants to keep a list of exemptions for free services, it should expand the list to include any other often-prohibited individuals and organizations. Specifically, 31 CFR 515.578(a)(4)(i)—which allows Cuban government officials to use free services—should include the same language for the Cuba Restricted List and other existing lists that prohibit Cuban entities.

The Treasury should clarify that websites offering both free and paid services can offer their free version to users in sanctioned countries, including normally prohibited individuals. OFAC did not include this in its previous fact sheet on the internet and sanctions in Cuba. In May, the Treasury Department provided additional guidance on what counts as “widely available to the public at no cost to the user.” However, as we explain, it’s not entirely clear what this phrase means. Websites have different models for access: Some require accounts; others don’t. Some have multiple tiers; others may require a credit card to use a free tier.

We believe this would be a useful clarification. A free tier of a paid service should be considered “widely available to the public at no cost to the user.” OFAC should clarify that a free service that requires a user to make an account, but that doesn’t require the user to pay, should also be considered “widely available to the public at no cost to the user.”

We believe the exemption on internet-based learning should be unconditional, rather than applying only in cases where “the course content is at the undergraduate level or below.” Alternatively, OFAC should publish guidelines on how it would determine the educational level of courses.

Provide De-risking Assistance

The State Department should provide grants to develop Cuba-specific versions of digital platforms and provide guidance on sanctions-compliant web hosting infrastructure. For example, the VPN service Hola has a Russia-specific website, holavpnrussia.com (ironically, both websites are geoblocked in Cuba). Digital service providers can then block users from one version of their website and more easily control compliance on the other. We encourage similar programs for other sanctioned countries.

Increase Transparency

First, given statutory ambiguity, Congress should pass the Digital Platform Commission Act. There is no body that has the clear authority to regulate and enforce transparency on digital platforms. Such a body should require websites that are geoblocking to inform end users. Currently, it is unclear to users whether content is inaccessible due to transient network failures, government censorship, or geoblocking from the web server itself. Our conversations with local internet users indicate this is a significant problem. This would also help researchers studying and monitoring geoblocking in the future.

Avoid Securitizing Digital Infrastructure

If the United States wants Cubans to access digital services, it should stop preventing U.S.-Cuban digital connection. In 2022, against the recommendation of the Cuba Internet Task Force, Team Telecom blocked an internet cable from Cuba landing in Florida, forcing Cuban internet service providers to pursue an internet trunk cable to Martinique. While the U.S. encourages companies to provide digital services to Cuban citizens, it prevents the Cuban internet from directly connecting to existing U.S. infrastructure.

***

We introduce and explore a little-known threat to digital equality and freedom—websites geoblocking users in response to political risks from sanctions. U.S. policy prioritizes internet freedom and access to information in repressive regimes. Clarifying distinctions between free and paid websites, allowing trunk cables to repressive states, enforcing transparency in geoblocking, and removing ambiguity about sanctions compliance are concrete steps the U.S. can take to ensure it does not undermine its own aims.

– Harry Oppenheimer, Anna Ablove, Roya Ensafi, Published courtesy of Lawfare.