Knowing How Technology and Artificial Intelligence Have—and Have Not—Affected Jobs in Recent Decades Offers Insight into How They Could Affect the Future of Work

No matter how helpful it is, technology has always generated some worker anxiety. Tailors rioted against quick-stitching sewing machines in their day, and, centuries later, the invention of mechanical switching likely bred a quieter desperation among telephone switchboard operators before they were let go.

Today, artificial intelligence (AI) is prompting worker apprehension. Similar to machine operators just a decade ago, those employed in fields as varied as computer coding, accounting, media, graphic design, law, and medicine are confronted daily with news that their jobs are up for deep change or even deletion.

To add to growing understanding as to how AI could affect the American workforce, RAND Corporation researchers looked deeply into how technology, including AI, has affected occupations in recent history. The team compared approximately 18,000 task descriptions in the Department of Labor’s Occupational Information Network (O*NET) with 8 million technology patents awarded by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) between 1976 and 2020. The team sifted through the data using natural language processing (NLP), which is a field of AI that enables computers to understand human language, to find which human job tasks were exposed to technology—that is, the extent to which key occupational tasks performed by humans could be performed by the technology described in patents. They then used the AI Patent Dataset (AIPD) to examine the exposure of specific occupations to AI.

The following sections summarize what they found.

TECHNOLOGY HAS BEEN A CONTENDING JOB CANDIDATE FOR DECADES

The study found that 87 percent of occupations had at least some exposure to technology patents in 1976. By 1989, all occupations had some exposure to technology patents. This means that technology could perform many occupational tasks that were usually done by humans more than 20 years ago.

THE INTENSITY OF OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE TO TECHNOLOGY IS ALWAYS IN FLUX

The top ten occupations that are most exposed to technology have changed over time. Some highly exposed occupations in the 1980s, such as dental hygienists, became less exposed relative to other occupations by 2020. Other occupations, such as online merchants, are relatively new and thus were most exposed to technology as advances were made in that field by 2020.

NEW TECHNOLOGY DOESN’T NECESSARILY REDUCE THE NEED FOR HUMAN LABOR

The highly exposed occupations (shown in purple below) are those that O*NET projects will grow faster than the average occupation or have at least 100,000 job openings over the next decade. This suggests that new technology could even foster job growth in certain sectors.

Of course, occupational expansion still depends on factors beyond technology. The demand for specific goods and services, other technological changes, and events that are impossible to predict can also bear on occupational growth.

AI Capability Categories, Defined

AI technology in patents was placed into eight categories:

- Knowledge processing: representing and deriving new facts from knowledge bases

- Speech recognition: understanding speech and generating responses

- AI hardware: physical hardware designed specifically to implement AI software

- Evolutionary computation: mimicking evolution to solve problems

- Natural language processing: understanding and generating human language

- Machine learning: generating algorithms from data

- Computer vision: understanding images and videos

- Planning and control: determining and executing plans to achieve goals

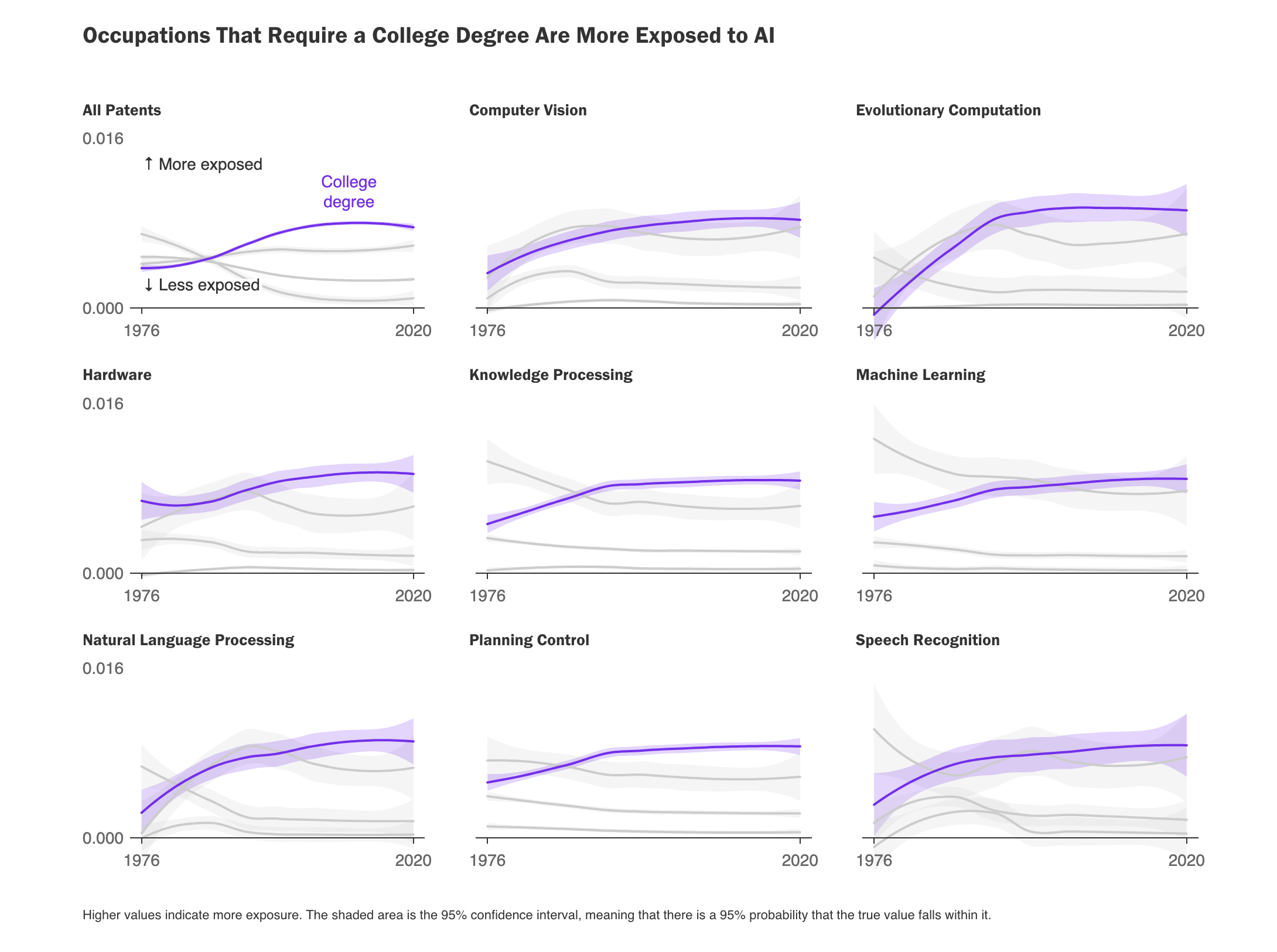

OCCUPATIONS THAT REQUIRE A COLLEGE DEGREE ARE MORE EXPOSED TO AI, BUT THIS TREND MIGHT BE CHANGING

For the past four decades, occupations that require a college degree have consistently been among the occupations that are most exposed to AI. While their rising trajectory has led them to become the most-exposed occupations as of 2020, this upward trend has flattened in recent years.

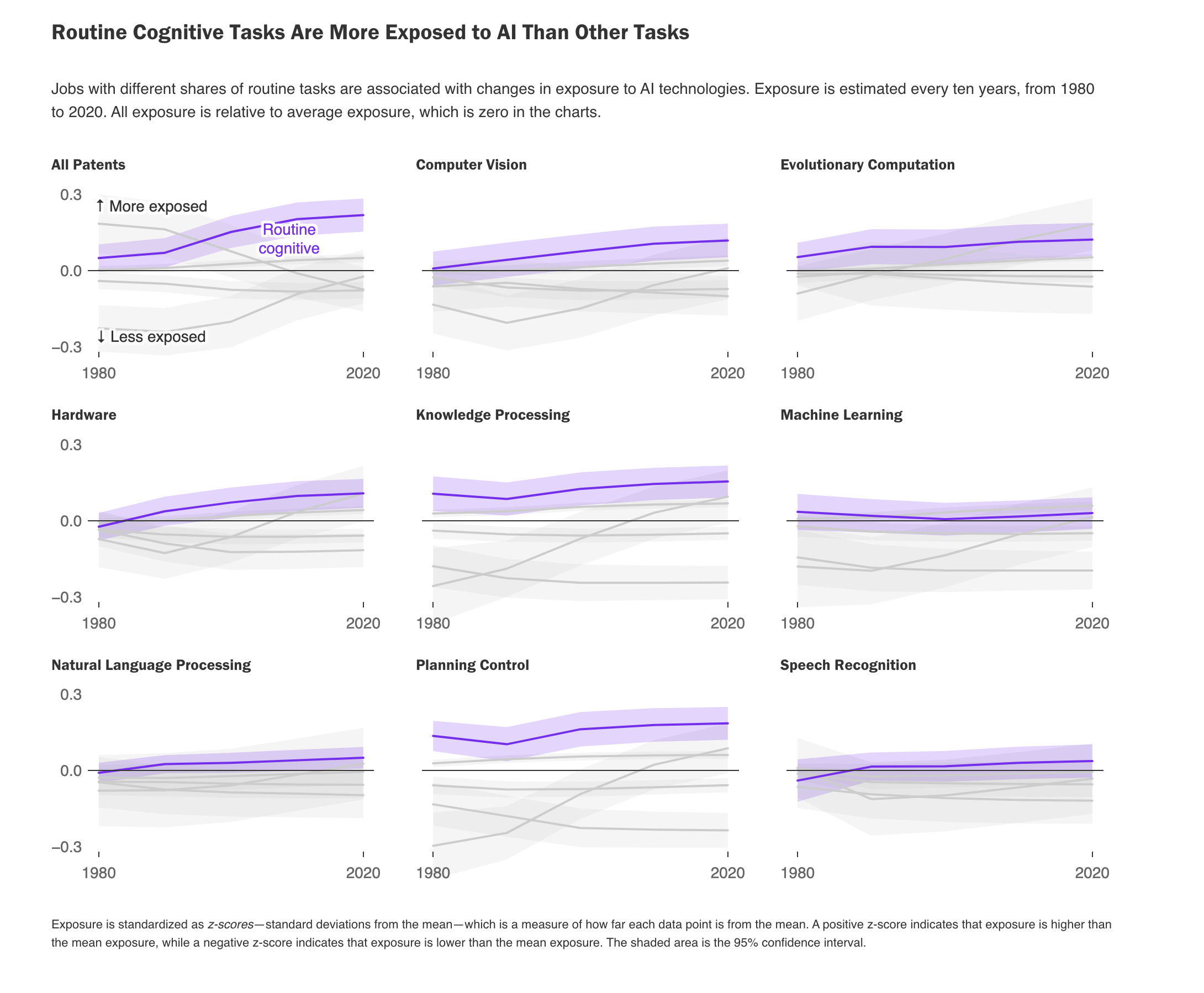

JOBS THAT HAVE A LOT OF ROUTINE COGNITIVE TASKS ARE MORE EXPOSED TO AI

The more routine a cognitive task is, the more likely it is to be exposed to AI patent technology. This connection has grown in magnitude since the 1980s. Examples of occupations with a high degree of routine cognitive tasks include bill and account collectors, proofreaders, and nuclear power reactor operators. Notably, the research team found that the opposite is true for manual labor: More-routine manual tasks have experienced a drop in exposure since the 1980s.

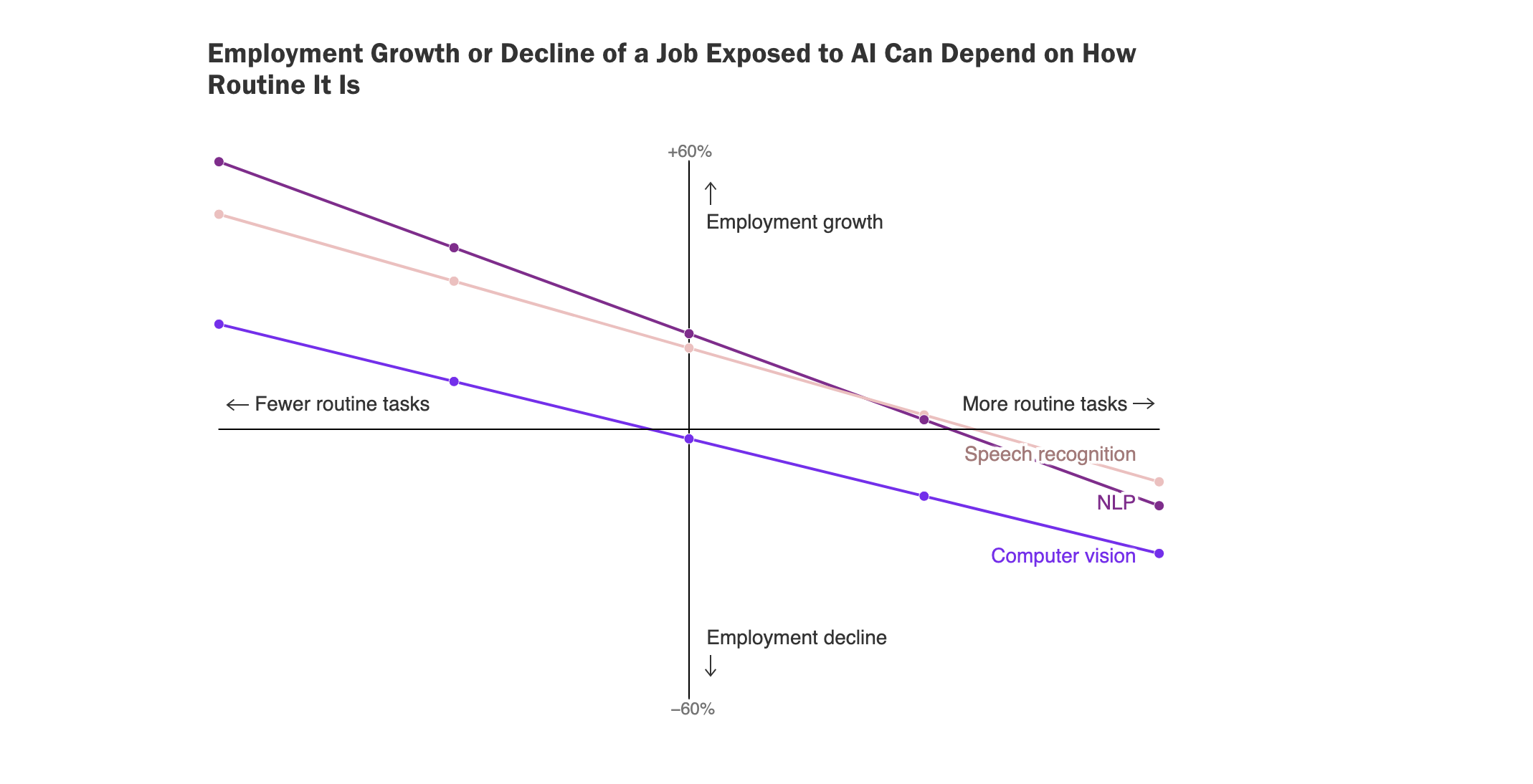

MORE-ROUTINE JOBS EXPOSED TO SOME TYPES OF AI ARE ASSOCIATED WITH EMPLOYMENT DECLINES

In general, an increase in exposure to AI technology has a mixed relationship with employment growth. However, jobs that are routine-intensive and have an increase in AI exposure in speech recognition, NLP, or computer vision capabilities are associated with recent declines in employment. For example, captioners (who create running transcripts of audio and video recordings for people who face challenges related to hearing or sight) are exposed to AI speech recognition, NLP, and computer vision, and could experience limited employment growth or even declines in the next few years.

These analyses of occupational tasks and technology patents offer a unique look at how technology has affected the U.S. workforce over the last 40 or more years. Importantly, it gives clues as to how developing AI capabilities could affect the workforce in the coming decades. Many occupations, especially those requiring educational investment after high school, are likely to be affected. The good news is that many of these jobs will not go away; more likely, they will morph into something else that employers need as more-routine cognitive tasks are passed on to AI. Workforce development programs and educators can adjust occupational training now to ready workers to focus on areas that require human-specific talent, such as critical thinking and collaboration with partners, whether AI or human.

Credits

Kate Giglio (writing), Alyson Youngblood (design), and Marissa Norris (production)

About the Research

This visualization is based on research by Tobias Sytsma and Éder M. Sousa.