A new battle is emerging between AI regulation optimists and AI regulation skeptics.

.jpeg?sfvrsn=f8ab7a0d_5)

In the tech sector, the political alliances that drive policymaking shift rapidly. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) is changing them again. These new dynamics will influence the scope and scale of AI regulation in the United States and throughout the world.

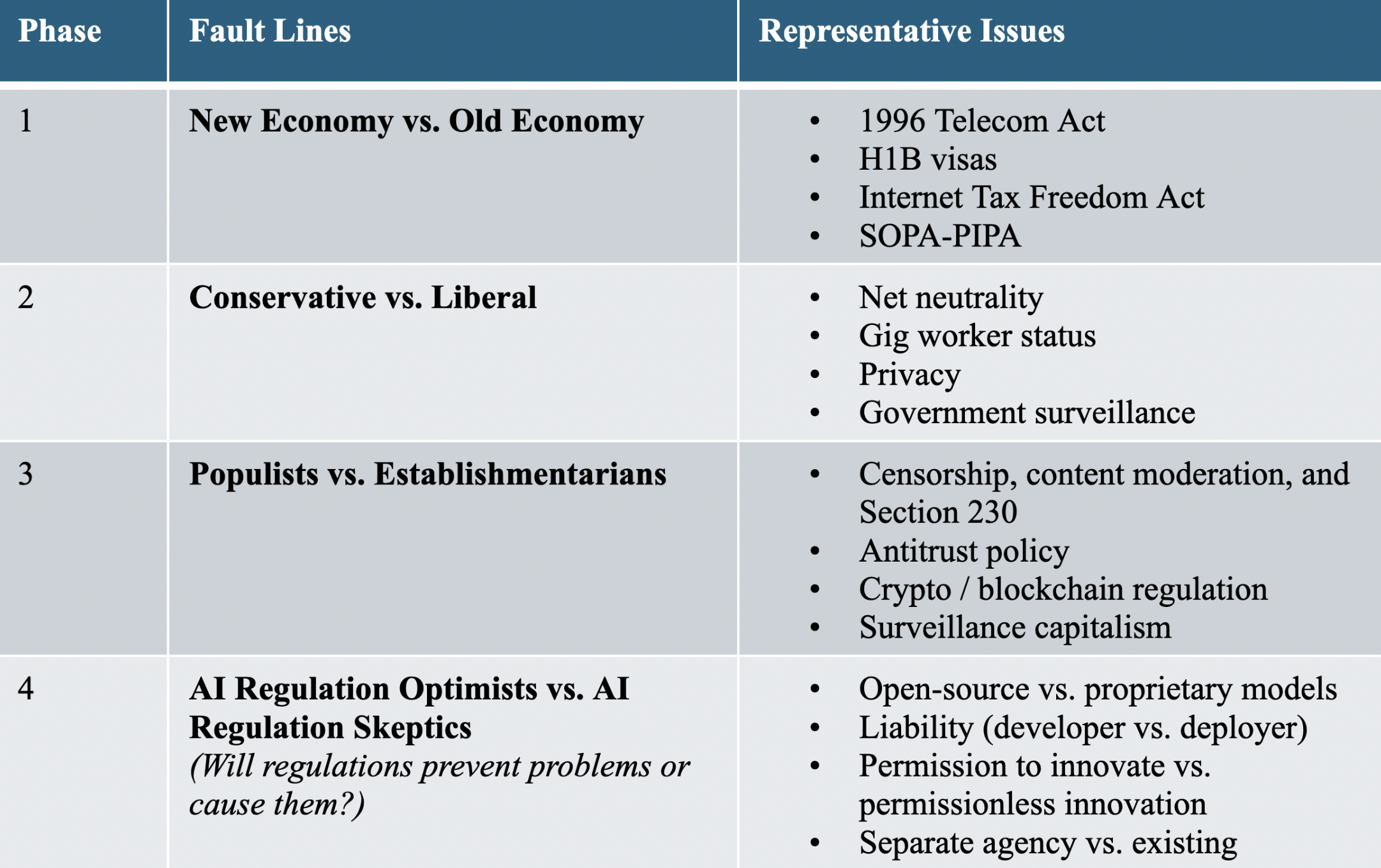

In the first phase of internet-era tech policy, large majorities on both the left (“new Democrats”) and the right (“free market conservatives”) viewed technology as a force for good and the companies that created tech products as the crown jewels of American entrepreneurship and ingenuity (see Table 1). New economy acolytes battled old economy advocates over immigration, intellectual property, taxation, and regulation, with a bipartisan majority believing that what’s good for the internet was good for America.

The second phase witnessed more traditional liberal-conservative divides. The left sought tighter rules to control what they perceived as market failures and protect consumers, such as net neutrality and privacy rules, while the right wanted less interference with free speech and free enterprise.

The third phase reflected the emergence of populism on both the left and right, concurrent with the increasing power of Big Tech across the economy and society. These divisions do not always break down along party lines: Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar finds common cause with Republican Sen. Josh Hawley on antitrust, while Democratic Sen. Richard Blumenthal partners with Republican Sen. Marsha Blackburn on kids’ online safety. Experts on the left, such as Matt Stoller, find unexpected allies on the right, such as the Heritage Foundation.

Table 1. Technology policy political divides, 1994-2024.

Artificial intelligence is ushering in a fourth phase in tech politics, and the changes are unfolding quickly. The generative AI hype-cycle kicked off with the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022. Nearly 18 months later, new alignments are already starting to emerge that present new fault lines in debates about the optimal governance for the tech sector. With new fault lines come new opportunities for new coalitions. Former adversaries may become allies; former allies may part ways.

Unlike tech policy alliances rooted in economic philosophies, political ideology, or concerns about corporate influence and concentration, the AI schism is anchored in vastly different conceptions about the proper balance between government-imposed rules and open market-driven innovation.

On one side are “AI regulation optimists”: those who believe that government is up to the challenge of devising new rules and oversight structures to manage what they see as unprecedented risks. Many AI regulation optimists are also bullish on AI technology, but they believe regulation is necessary to constrain risks, and they believe we need regulation as soon as possible to contain risks before they emerge.

On the other side are “AI regulation skeptics”: those who fear new government rules will quash innovation, entrench larger platforms, and make it harder for startups to compete. The skeptics believe that openness will unlock the benefits of AI for society better than tight government oversight and that rules will stifle innovation and lead to further market concentration. The skeptics are pessimistic about the impact that government actors will have but optimistic about the impact the technology will have on our society.

This framework helps explain substantive alliances in the industry that even a year ago seemed impossible, as lawmakers, academics, think tanks, and civil society organizations try to adapt to new challenges and a new playing field.

For instance, in a report on large language models (LLMs) and generative AI, the U.K. Parliament warned that the “risk of regulatory capture is real and growing.” In support of that argument, it cites evidence submitted by Andreesen Horowitz, a leading venture capital firm co-founded by Marc Andreesen, a serial entrepreneur, vocal libertarian, and funder of AI startups. AI, in Marc Andreesen’s view, will save the world. In its submission to the U.K. Parliament, Andreesen Horowitz states that large AI companies must “not [be] allowed to establish a government-protected cartel that is insulated from market competition due to speculative claims of AI risk.”

The report also references evidence submitted by the Open Markets Institute (OMI), which is arguably the intellectual epicenter of the Neo-Brandeisian antitrust reform movement. Its director, Barry Lynn, was an early mentor to Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chair Lina Khan, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) speaks regularly at their events. OMI is deeply skeptical of corporate concentration and corporate influence, and to date, Marc Andreesen and Barry Lynn have rarely been aligned on tech policy.

Yet the U.K. Parliament report cites evidence submitted by OMI alongside its citation of Andreesen Horowitz. It writes that OMI “similarly raised concerns that incumbents may ‘convert their economic heft into regulatory influence’ and distract policymakers ‘with far-off, improbable risks.’” On this issue, OMI and Andreesen Horowitz are cited side-by-side for the same idea. They are both AI regulation skeptics.

The emergence of these new alliances has begun to shape the contours of AI regulation. Sen. Klobuchar, who has introduced a wide array of proposals to address her concerns about anti-competitive conduct in the tech sector, and Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.), who did not support those bills, recently introduced a new bill on AI accountability. They couldn’t find a way to work together on app stores, self-preferencing, or online news—but they found a path on AI.

Sometimes, the new alliances are between lawmakers and companies. Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) introduced a bill to create a federal agency to govern AI. Typically those types of proposals to expand the federal bureaucracy are met with industry resistance, but Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, dangled similar ideas in his congressional testimony last May. So did Microsoft President Brad Smith, in a blog post around the same time.

In opposition to the proposal, Republicans and Democrats such as Jay Obernolte (R-Calif.) and Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.) have argued that lawmakers should focus on providing resources to existing agencies, rather than trying to create new ones. And former Federal Communications Commission Chair Tom Wheeler, who has long advocated for the creation of a new agency to govern social media companies, supported the general concept of an AI governance body, but expressed skepticism about the idea of an AI agency granting “golden ticket” licenses to large developers. He has also warned of the risk that an agency granting licenses can be easily captured, arguing that “[c]reating a regulatory moat has the added advantage of occurring in a forum where the political influence of the big companies can be deployed.”

The traditional camps—new economy versus old economy, right versus left, populist versus establishmentarian—cannot fully explain these new divides. The new dividing line is between those who are first and foremost optimistic about regulation and those who are skeptical: those who believe that new rules will protect society from harm versus those who believe that new rules will protect established companies from competition.

The people who work in tech policy are still in the early stages of realizing the ways in which AI has scrambled tech politics. As this fourth divide solidifies, it is likely that there will be more and more examples of unexpected bedfellows.

Larger companies may work more closely with safety organizations, pushing for more stringent regulatory models. They may occasionally align with those who fear AI and see stringent new rules as critical to protecting society. Libertarian think tanks might find themselves on the signature line of advocacy letters with progressive organizations in the “hipster antitrust” movement, sounding the alarm about regulatory capture and the possibility of increased concentration in the tech market. Some of the antitrust experts who have been skeptical of antitrust enforcement against Big Tech may see more value in using antitrust enforcement to promote innovation in AI markets.

These fledgling alliances are new and evolving. It is not yet clear which ones are strong and which are weak, or how influential they’ll be. Relative strength will matter: One lesson from the third divide is how quickly effective advocates can change the dialogue and the policy reality. The Neo-Brandeisian antitrust movement once stood at the fringes of antitrust. Now, Lina Khan is the chair of the FTC.

It is not yet clear whether these new alliances will hold and, if they do, for how long. As is always the case in the tech sector, the future is uncertain and fragile. Dramatic events have shifted the tech policy landscape in the past, such as the 9/11 attacks, the Edward Snowden disclosures, the Apple encryption standoff, and the Russian disinformation campaigns in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. If the upcoming U.S. election is disrupted by an influence campaign that uses AI, if there is a massive data breach involving AI, or if AI-generated misinformation is linked to harm to a minor, the politics of AI may shift again.

But at least for now, the startling reality is that AI seems to be creating a new divide in tech politics that will spawn new alliances and coalitions, sometimes between people who previously worked on opposite sides of tech policy issues. These shifting allegiances will likely shape the arc of AI policy in the months —and possibly years—ahead.

– Bruce Mehlman, Matt Perault, Published courtesy of Lawfare.